- Home

- Features

- Startup Zone

- Projects

- Policies

- Shop

- Policies

- Projects

- Startup Zone

- Country Spotlight

- Analysis

- Tech

- Policies

- Projects

- Startup Zone

- Country Spotlight

- Analysis

- More

- Beyond the Kalashnikov: Africa’s Shift Toward Technology-Driven Warfare

- Afrail Express: Uniting a Continent on Rails

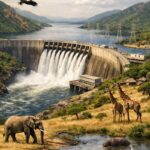

- AFRICA’S ENERGY CORRIDORS: CONNECTING POWER, PEOPLE, AND PROSPERITY

- Startup Lions Campus: Empowering Kenya’s Digital Generation

- L’Art de Vivre’s Le Paradis de Mahdia: Tunisia’s Model for Sustainable Luxury

- The Lobito Corridor: Rewiring Africa’s Trade Arteries Through Strategic Infrastructure

- AFRICA’S GREEN ENERGY TRANSITION: A BEACON OF HOPE FOR CLIMATE ACTION

- Dangote Refinery: Showcasing Africa’s Project Success Story

- AFRICA GREEN ECONOMY: ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW

- The Most Important Amicus Brief in the History of the World

- The Rise of Indigenous UAVs: Africa’s Drone Capabilities in Warfare and Surveillance

- AFRICA’S LARGEST OIL PRODUCERS: A COMPREHENSIVE OVERVIEW

- Beyond the Kalashnikov: Africa’s Shift Toward Technology-Driven Warfare

- Afrail Express: Uniting a Continent on Rails

- AFRICA’S ENERGY CORRIDORS: CONNECTING POWER, PEOPLE, AND PROSPERITY

- Startup Lions Campus: Empowering Kenya’s Digital Generation

- L’Art de Vivre’s Le Paradis de Mahdia: Tunisia’s Model for Sustainable Luxury

- The Lobito Corridor: Rewiring Africa’s Trade Arteries Through Strategic Infrastructure

- AFRICA’S GREEN ENERGY TRANSITION: A BEACON OF HOPE FOR CLIMATE ACTION

- Dangote Refinery: Showcasing Africa’s Project Success Story

- AFRICA GREEN ECONOMY: ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW

- The Most Important Amicus Brief in the History of the World

- The Rise of Indigenous UAVs: Africa’s Drone Capabilities in Warfare and Surveillance

- AFRICA’S LARGEST OIL PRODUCERS: A COMPREHENSIVE OVERVIEW

- Beyond the Kalashnikov: Africa’s Shift Toward Technology-Driven Warfare

- Afrail Express: Uniting a Continent on Rails

- AFRICA’S ENERGY CORRIDORS: CONNECTING POWER, PEOPLE, AND PROSPERITY

- Startup Lions Campus: Empowering Kenya’s Digital Generation

- L’Art de Vivre’s Le Paradis de Mahdia: Tunisia’s Model for Sustainable Luxury

- The Lobito Corridor: Rewiring Africa’s Trade Arteries Through Strategic Infrastructure

- Startup Zone

Top Insights

Tunisia’s Water Desalination Drive Amid Climate Pressures

Water scarcity remains a profound challenge for Tunisia, driven by climate change, environmental degradation, and policy shortcomings. As the country faces its most severe drought in recorded history, Tunisia has embarked on an ambitious water management strategy centred on expanding desalination technology. Currently, desalination plants contribute approximately 6% of the nation’s freshwater supply, with a strategic goal to boost this share to 30% by 2030. This initiative is part of a broader framework that includes wastewater treatment, renewable energy integration, and sustainable resource management, all aimed at safeguarding food security and socio-economic stability.

The Context of Water Scarcity in Tunisia

Climate Change and Drought

Tunisia is experiencing its worst recorded drought, with rainfall declining sharply over the past decades. Climate models project increasing temperatures and irregular precipitation patterns, intensifying water stress. The country’s arid and semi-arid zones, which occupy over 80% of its territory, are particularly vulnerable to prolonged dry spells and heatwaves. These environmental pressures threaten agriculture—the backbone of Tunisia’s economy—and urban water supplies, risking food insecurity and socio-economic destabilisation.

READ ALSO: Nigeria’s Drought Mitigation Infrastructure in Northern States

Historical and Policy-Driven Water Challenges

Despite the urgency, Tunisia’s water crisis is largely rooted in policy failures rather than solely in climate effects. Since independence in 1956, successive governments have prioritised water mobilisation for agriculture and industry, often at the expense of equitable domestic supply and ecosystem health. Heavy reliance on groundwater extraction, mismanagement of surface water, and export-driven agriculture have depleted aquifers and degraded water quality.

Foreign influence, particularly from international financial institutions like the World Bank, has played a significant role in shaping water policies. These policies often emphasise privatisation, infrastructure projects, and market-driven approaches, which tend to favour foreign investors and wealthy elites, sometimes neglecting rural and vulnerable populations.

Tunisia’s Desalination Strategy: A Response to Climate-Induced Stress

Current Status and Ambitions

• Existing Infrastructure: Tunisia’s desalination capacity currently accounts for about 6% of its total freshwater, primarily serving urban centres like Tunis and coastal industries.

• Target Growth: The national water plan aims to increase desalination’s contribution to 30% of the water supply by 2030. This includes constructing new plants, upgrading existing facilities, and integrating renewable energy sources.

Technological Approaches

• Reverse Osmosis (RO): The dominant technology due to its cost-effectiveness and scalability. RO plants are being installed along the coast, supplying water for urban and industrial uses.

• Thermal Desalination (MSF and MED): Deployed in larger plants, often powered by waste heat or fossil fuels. These are suitable for high-volume needs but pose environmental and economic challenges.

• Emerging Technologies: Solar-powered desalination (e.g., humidification-dehumidification or HDH systems) is gaining attention, aligning with Tunisia’s abundant solar resources. Pilot projects aim to demonstrate viability, reduce energy costs, and minimise environmental impacts.

Coupling Desalination with Renewable Energy

Recognising the environmental footprint of desalination, Tunisia is investing in solar and wind energy integration. Solar PV and concentrated solar power (CSP) plants are being connected to desalination facilities to reduce reliance on fossil fuels, lowering greenhouse gas emissions and operational costs. This transition aligns with global efforts to promote sustainable water management and climate mitigation.

Wastewater Treatment and Reuse

Complementing desalination, Tunisia is expanding wastewater recycling programs to reduce pressure on freshwater sources. Treated effluent is increasingly used for agriculture and industry, especially in water-scarce regions where desalination alone cannot meet the demand.

Challenges Facing Desalination Expansion

Environmental Concerns

• Brine Discharge: The concentrated salt brine produced by desalination can harm marine ecosystems if not properly managed. Developing environmentally sound disposal methods is crucial.

• Energy Consumption: Desalination is energy-intensive; thus, reliance on fossil fuels can undermine climate goals unless renewable sources are prioritised.

Economic and Technological Barriers

• High Capital Costs: Building large-scale desalination plants requires substantial investment, often financed by foreign aid, loans, or public-private partnerships.

• Operational Costs: Maintenance, energy, and infrastructure costs pose ongoing financial burdens, especially in regions with limited fiscal capacity.

Policy and Social Issues

• Equity of Access: Ensuring that rural and marginalised populations benefit from desalination is a persistent challenge, as most plants are located near urban centres.

• Sustainability of Water Resources: Over-reliance on desalination without integrated water management risks neglecting demand-side measures like water conservation and efficient agriculture.

Broader Implications of External Influence

Role of International Donors and Policies

The World Bank and other donors have historically promoted water infrastructure projects in Tunisia, emphasising privatisation, market liberalisation, and private sector involvement. While these policies aim to improve efficiency, they often prioritise economic returns over social equity and environmental sustainability.

Research indicates that such strategies have sometimes led to increased water costs for consumers, reduced access for the poor, and environmental degradation due to inadequate regulation of brine disposal and energy use. The global agenda of water commodification can conflict with local needs for equitable access and ecological preservation.

Economic and Social Impacts

Foreign-driven policies have contributed to a water management model that favours export-oriented agriculture and industrialisation, often at the expense of local populations’ access to safe, affordable water. This dynamic exacerbates social inequalities, fuels rural-urban divides, and hampers efforts to build resilience against climate shocks.

Pathways to Sustainable Water Management

Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM)

• Developing regional cooperation frameworks to share transboundary water resources and aquifers.

• Prioritising demand management, including water-saving technologies, public awareness campaigns, and regulatory measures.

• Promoting ecosystem-based approaches to maintain natural water cycles and recharge groundwater.

Technological Innovation and Renewable Energy

• Scaling up solar-powered desalination and wastewater reuse projects.

• Investing in research to develop low-energy, environmentally friendly desalination methods.

• Incorporating smart water grids and real-time monitoring systems for efficient resource allocation.

Policy Reforms and Local Engagement

• Reassessing foreign influence to ensure policies serve national and local interests.

• Strengthening legal frameworks to regulate environmental impacts, water pricing, and access equity.

• Engaging local communities, farmers, and marginalised groups in water governance to foster inclusive decision-making.

Tunisia’s reliance on desalination as a core component of its water strategy is both a response to climate pressures and a reflection of deep-rooted policy and management failures. While technological advances and renewable energy integration hold promise, sustainable water security in Tunisia requires a comprehensive approach that balances supply-side innovations with demand management, ecological preservation, and social equity.

Addressing the climate crisis demands that Tunisia not only expand desalination but also reform its water policies, foster regional cooperation, and ensure that external financial and political influences align with national sovereignty and development goals. Only through integrated, sustainable, and inclusive strategies can Tunisia secure its water future amid mounting climate pressures.

Recent Posts

Related Articles

Cutting-Edge Environmental Conservation Projects and Their Champions

Environmental conservation has entered a decisive era. As climate change accelerates, biodiversity...

ByafricaprojectJanuary 28, 2026Clean Water Access Projects Improving Lives in Underserved Regions

Access to clean and reliable water remains one of Africa’s most pressing...

ByafricaprojectJanuary 19, 2026Industrial Corridors Attracting Global Investors

Across Africa, industrial corridors are emerging as strategic economic arteries driving industrialization,...

ByafricaprojectJanuary 16, 2026The Engineers Behind Africa’s Tallest and Most Iconic Towers

Across Africa, the rise of tall and iconic towers is reshaping skylines...

ByafricaprojectJanuary 15, 2026