- Home

- Features

- Startup Zone

- Projects

- Policies

- Shop

- Policies

- Projects

- Startup Zone

- Country Spotlight

- Analysis

- Tech

- Policies

- Projects

- Startup Zone

- Country Spotlight

- Analysis

- More

- Beyond the Kalashnikov: Africa’s Shift Toward Technology-Driven Warfare

- Afrail Express: Uniting a Continent on Rails

- AFRICA’S ENERGY CORRIDORS: CONNECTING POWER, PEOPLE, AND PROSPERITY

- Startup Lions Campus: Empowering Kenya’s Digital Generation

- L’Art de Vivre’s Le Paradis de Mahdia: Tunisia’s Model for Sustainable Luxury

- The Lobito Corridor: Rewiring Africa’s Trade Arteries Through Strategic Infrastructure

- AFRICA’S GREEN ENERGY TRANSITION: A BEACON OF HOPE FOR CLIMATE ACTION

- Dangote Refinery: Showcasing Africa’s Project Success Story

- AFRICA GREEN ECONOMY: ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW

- The Most Important Amicus Brief in the History of the World

- The Rise of Indigenous UAVs: Africa’s Drone Capabilities in Warfare and Surveillance

- AFRICA’S LARGEST OIL PRODUCERS: A COMPREHENSIVE OVERVIEW

- Beyond the Kalashnikov: Africa’s Shift Toward Technology-Driven Warfare

- Afrail Express: Uniting a Continent on Rails

- AFRICA’S ENERGY CORRIDORS: CONNECTING POWER, PEOPLE, AND PROSPERITY

- Startup Lions Campus: Empowering Kenya’s Digital Generation

- L’Art de Vivre’s Le Paradis de Mahdia: Tunisia’s Model for Sustainable Luxury

- The Lobito Corridor: Rewiring Africa’s Trade Arteries Through Strategic Infrastructure

- AFRICA’S GREEN ENERGY TRANSITION: A BEACON OF HOPE FOR CLIMATE ACTION

- Dangote Refinery: Showcasing Africa’s Project Success Story

- AFRICA GREEN ECONOMY: ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW

- The Most Important Amicus Brief in the History of the World

- The Rise of Indigenous UAVs: Africa’s Drone Capabilities in Warfare and Surveillance

- AFRICA’S LARGEST OIL PRODUCERS: A COMPREHENSIVE OVERVIEW

- Beyond the Kalashnikov: Africa’s Shift Toward Technology-Driven Warfare

- Afrail Express: Uniting a Continent on Rails

- AFRICA’S ENERGY CORRIDORS: CONNECTING POWER, PEOPLE, AND PROSPERITY

- Startup Lions Campus: Empowering Kenya’s Digital Generation

- L’Art de Vivre’s Le Paradis de Mahdia: Tunisia’s Model for Sustainable Luxury

- The Lobito Corridor: Rewiring Africa’s Trade Arteries Through Strategic Infrastructure

- Startup Zone

Top Insights

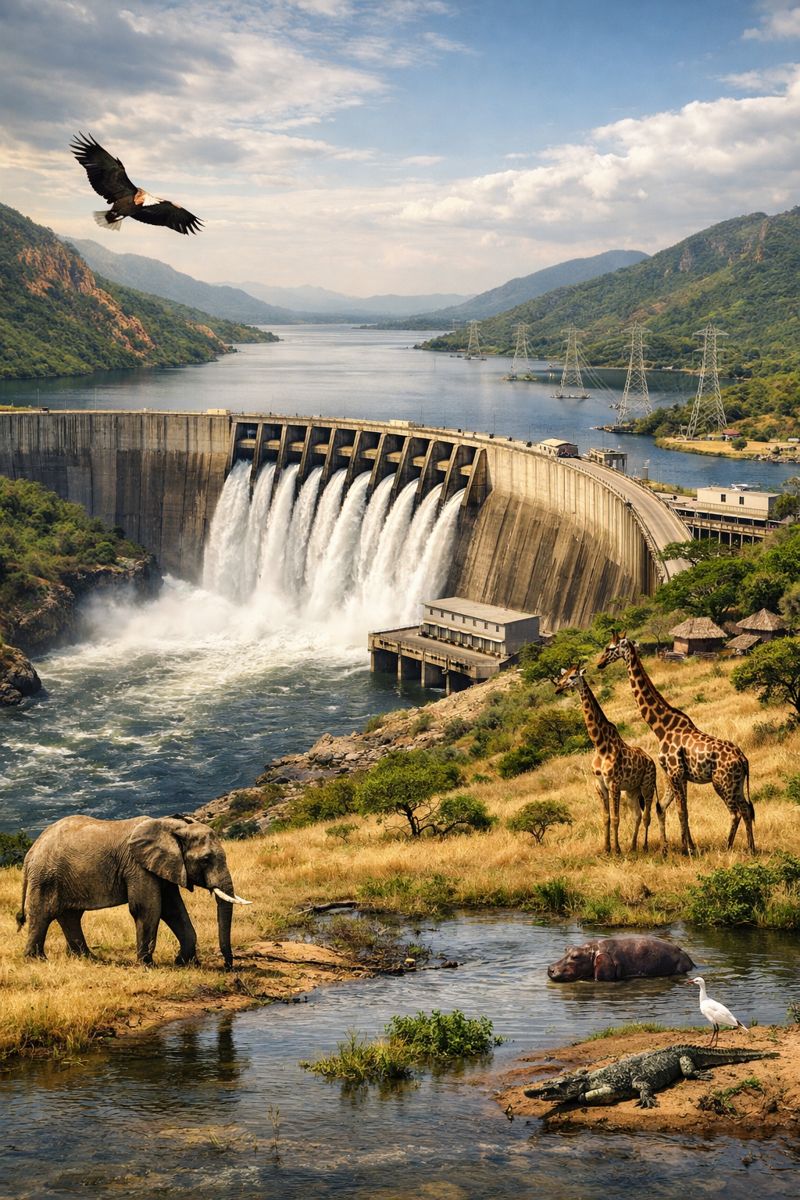

Africa’s Mega Dams: Balancing Development and Environmental Needs

Large-scale hydropower dams have become central to Africa’s development strategy as governments pursue reliable electricity, water security, and climate-resilient infrastructure. From the Nile Basin to the Zambezi and Congo river systems, these mega projects promise to power industrialization, support urban expansion, and reduce dependence on fossil fuels. Yet, they also raise significant environmental and social concerns, underscoring the complex balance between urgent development needs and the protection of ecosystems and communities.

Africa continues to face a major electricity deficit that constrains economic growth and quality of life. Hundreds of millions of people lack reliable power, while industries struggle with high energy costs and frequent outages. Mega dams appear attractive because they generate large volumes of renewable energy at low long-term operating costs. Projects such as Ethiopia’s Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Zambia and Zimbabwe’s Kariba Dam, and Mozambique’s Cahora Bassa Dam are designed not only to power domestic grids but also to supply regional electricity markets. This makes hydropower a cornerstone of continental integration and industrial expansion.

Related Articles: Cutting-Edge Environmental Conservation Projects and Their Champions

Beyond energy generation, mega dams play a crucial role in water management. Many African countries experience cycles of droughts and floods that threaten agriculture, settlements, and livelihoods. Large reservoirs can regulate river flows, reduce flood risks, and provide irrigation during dry seasons. For countries with growing populations and food security challenges, the multipurpose benefits of dams strengthen the case for their high upfront costs. As a result, governments and development banks often frame dams as essential infrastructure for climate adaptation.

However, the environmental impacts of mega dams are far-reaching and often irreversible. Reservoirs disrupt natural river ecosystems, alter sediment flows, and affect downstream water quality. These changes can undermine fisheries, wetlands, and floodplain systems that support biodiversity and local economies. In the Nile and Zambezi basins, downstream communities and governments have raised concerns that upstream dams may reduce water availability or disrupt seasonal flooding vital for agriculture. Environmental scientists caution that cumulative impacts from multiple dams within a single basin can magnify ecological degradation.

The social consequences are equally profound. Mega dam construction frequently displaces thousands—sometimes hundreds of thousands—of people. Displaced communities often lose access to fertile land, fisheries, and cultural heritage sites. Although compensation and resettlement plans are typically included in project designs, implementation is uneven. Some communities face long-term impoverishment and social dislocation, raising questions about equity and whose development priorities are truly served.

Climate change complicates the hydropower debate further. While hydropower is promoted as a low-carbon energy source, shifting rainfall patterns and prolonged droughts threaten its reliability. Reduced reservoir levels can undermine electricity generation and financial viability. Additionally, reservoirs in tropical regions can emit methane—a potent greenhouse gas—due to decomposing submerged vegetation. These realities challenge the perception of mega dams as a uniformly clean energy option.

In response, there is growing emphasis on better governance, planning, and environmental safeguards. Strategic environmental assessments at the river-basin scale are increasingly recommended to evaluate cumulative impacts and avoid zero-sum outcomes. Transboundary river cooperation—supported by regional bodies and basin organizations—helps build trust, coordinate development, and improve data sharing.

Technological innovations also offer mitigation possibilities. Modern dam designs incorporate environmental flow releases to mimic natural river rhythms, while fish passages, sediment management systems, and adaptive reservoir operations help reduce ecological harm. Complementing hydropower with decentralized renewable energy—particularly solar and wind—can enhance resilience and reduce overdependence on mega dams.

Ultimately, the future of Africa’s mega dams rests on a more inclusive and balanced development approach. Transparent decision-making, meaningful community engagement, and strong environmental monitoring are essential for long-term sustainability. Mega dams can support Africa’s energy security, climate resilience, and regional integration, but only when their economic benefits are weighed carefully against social and ecological costs.

In conclusion, Africa’s mega dams embody both promise and risk. They offer powerful tools for development but pose equally serious challenges for ecosystems and vulnerable communities. Achieving the right balance requires holistic planning that recognizes rivers as living systems and communities as central stakeholders. With foresight, accountability, and diversified energy strategies, mega dams can contribute to a sustainable and inclusive future for the continent.

Recent Posts

Related Articles

AfCFTA and Its Impact on Africa’s Infrastructure Policies

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which came into force in...

ByafricaprojectSeptember 25, 2025The Battle Over Energy Subsidies in Africa: Who Wins and Who Loses?

Energy subsidies have long been a contentious topic in African economies, representing...

ByafricaprojectSeptember 24, 2025Pipeline Politics: The Future of Africa’s Oil and Gas Infrastructure

Africa’s oil and gas sector is undeniably at a pivotal crossroads, with...

ByafricaprojectSeptember 22, 2025The Impact of ESG Policies on Africa’s Oil Sector

In recent years, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) considerations have surged in...

ByafricaprojectSeptember 19, 2025

Leave a comment