- Home

- Features

- Startup Zone

- Projects

- Policies

- Shop

- Policies

- Projects

- Startup Zone

- Country Spotlight

- Analysis

- Tech

- Policies

- Projects

- Startup Zone

- Country Spotlight

- Analysis

- More

- Beyond the Kalashnikov: Africa’s Shift Toward Technology-Driven Warfare

- Afrail Express: Uniting a Continent on Rails

- AFRICA’S ENERGY CORRIDORS: CONNECTING POWER, PEOPLE, AND PROSPERITY

- Startup Lions Campus: Empowering Kenya’s Digital Generation

- L’Art de Vivre’s Le Paradis de Mahdia: Tunisia’s Model for Sustainable Luxury

- The Lobito Corridor: Rewiring Africa’s Trade Arteries Through Strategic Infrastructure

- AFRICA’S GREEN ENERGY TRANSITION: A BEACON OF HOPE FOR CLIMATE ACTION

- Dangote Refinery: Showcasing Africa’s Project Success Story

- AFRICA GREEN ECONOMY: ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW

- The Most Important Amicus Brief in the History of the World

- The Rise of Indigenous UAVs: Africa’s Drone Capabilities in Warfare and Surveillance

- AFRICA’S LARGEST OIL PRODUCERS: A COMPREHENSIVE OVERVIEW

- Beyond the Kalashnikov: Africa’s Shift Toward Technology-Driven Warfare

- Afrail Express: Uniting a Continent on Rails

- AFRICA’S ENERGY CORRIDORS: CONNECTING POWER, PEOPLE, AND PROSPERITY

- Startup Lions Campus: Empowering Kenya’s Digital Generation

- L’Art de Vivre’s Le Paradis de Mahdia: Tunisia’s Model for Sustainable Luxury

- The Lobito Corridor: Rewiring Africa’s Trade Arteries Through Strategic Infrastructure

- AFRICA’S GREEN ENERGY TRANSITION: A BEACON OF HOPE FOR CLIMATE ACTION

- Dangote Refinery: Showcasing Africa’s Project Success Story

- AFRICA GREEN ECONOMY: ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW

- The Most Important Amicus Brief in the History of the World

- The Rise of Indigenous UAVs: Africa’s Drone Capabilities in Warfare and Surveillance

- AFRICA’S LARGEST OIL PRODUCERS: A COMPREHENSIVE OVERVIEW

- Beyond the Kalashnikov: Africa’s Shift Toward Technology-Driven Warfare

- Afrail Express: Uniting a Continent on Rails

- AFRICA’S ENERGY CORRIDORS: CONNECTING POWER, PEOPLE, AND PROSPERITY

- Startup Lions Campus: Empowering Kenya’s Digital Generation

- L’Art de Vivre’s Le Paradis de Mahdia: Tunisia’s Model for Sustainable Luxury

- The Lobito Corridor: Rewiring Africa’s Trade Arteries Through Strategic Infrastructure

- Startup Zone

Top Insights

AFRICA’S MEGA ROAD PROJECTS: CORRIDORS OPENING UP TRADE, TOURISM, AND REGIONAL INTEGRATION

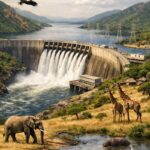

Across Africa, a quiet transformation is taking place on newly laid asphalt. Governments, regional blocs, and global financiers are investing billions in cross-border highway corridors designed to connect economies long divided by colonial borders, inadequate infrastructure, and cycles of conflict. Stretching from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, these mega road projects are being framed not just as transport links, but as catalysts for trade, tourism, and deeper regional integration under the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

At the center of this push is the revitalization of the Trans-African Highway network a mid-20th-century ambition now receiving renewed momentum. Key routes such as the Cairo-to-Cape Town, Lagos-Mombasa, and Dakar-Lagos corridors are undergoing major upgrades. The 4,500 km Lagos-Dakar highway, frequently referred to as the Abidjan-Lagos Corridor, is finally progressing beyond planning stages. Co-funded by the African Development Bank and the European Union, the six participating countries Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, Benin, Nigeria, and Senegal are harmonizing road standards to create a seamless coastal highway. Once completed, the project is expected to reduce travel time between Lagos and Abidjan from several days to under 24 hours.

Related Article: AFRICA’S PORT MODERNIZATION DRIVE: PROJECTS PREPARING THE CONTINENT FOR GLOBAL TRADE

Further east, Kenya’s Lamu Port–South Sudan–Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) corridor one of East Africa’s most ambitious infrastructure ventures continues to advance in phases. Estimated at $25 billion, LAPSSET includes the new deep-water port at Lamu, an oil pipeline, a railway, and a 1,700 km highway linking Ethiopia and South Sudan to the Indian Ocean. When fully operational, the corridor could lower Ethiopia’s transport costs by as much as 40 percent while opening northern Kenya’s vast semi-arid regions to tourism, renewable energy projects, and agro-industrial investment.

Southern Africa is also modernizing one of its most vital arteries: the North-South Corridor, running from Durban through Botswana, Zambia, and into the mineral-rich Democratic Republic of Congo. With support from Chinese financing and South African engineering firms, the project aims to improve a corridor that already handles roughly 70 percent of the region’s road freight. Upgrades to border posts particularly at Beitbridge and Chirundu, long notorious for multi-day truck delays are central to this effort. Newly established one-stop border facilities and digital customs systems have already reduced clearance times from several days to mere hours.

Tourism, too, is emerging as a significant beneficiary of better roads. The improved Walvis Bay–Ndola–Lubumbashi corridor, which cuts through Namibia, Zambia, and the DRC, has revived overland tourism through the Caprivi Strip, attracting self-drive visitors heading toward Victoria Falls and the Okavango Delta. Likewise, upgrades to the Great North Road, stretching from Tanzania through Zambia to South Africa, are drawing adventure travelers who previously relied on air travel between safari destinations. Hospitality operators ranging from boutique lodges to major hotel chains report rising occupancy along newly paved routes, demonstrating how road access can expand tourism beyond traditional, high-end fly-in markets.

Despite the optimism, mega-road projects face significant scrutiny. Environmental groups have challenged sections of LAPSSET that threaten indigenous forests and wildlife migration paths, including critical elephant corridors. Along the Abidjan-Lagos highway, some affected communities have protested what they consider inadequate compensation for land acquisition. Debt analysts also warn that heavy borrowing from China and other lenders may place long-term financial pressure on countries if projected trade gains fall short. Corruption concerns persist as well, fueled in part by cost overruns and procurement controversies on parallel infrastructure projects such as Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway.

Social impacts are increasingly part of the conversation. Research along the Nairobi-Addis Ababa highway shows that improved connectivity boosts market access for women traders who form a large share of cross-border micro-entrepreneurs. However, the same studies indicate heightened risks of harassment and extortion at checkpoints. In response, development agencies and local governments are piloting interventions including women-only waiting areas, community-led monitoring, and digital payment systems to reduce reliance on cash and improve traveler safety.

Nearly a decade after the AfCFTA’s launch, Africa is slowly building the physical infrastructure needed to unlock truly integrated continental trade. While challenges remain financial, environmental, and social the momentum behind these corridors marks a decisive shift toward connectivity-driven development. As the final stretches are paved and borders become easier to cross, such projects may do more than move goods and people. They may reshape long-held perceptions of a fragmented continent, revealing instead a network of interconnected regions whose future growth depends on the roads now under construction.

Recent Posts

Related Articles

Cutting-Edge Environmental Conservation Projects and Their Champions

Environmental conservation has entered a decisive era. As climate change accelerates, biodiversity...

ByafricaprojectJanuary 28, 2026Clean Water Access Projects Improving Lives in Underserved Regions

Access to clean and reliable water remains one of Africa’s most pressing...

ByafricaprojectJanuary 19, 2026Industrial Corridors Attracting Global Investors

Across Africa, industrial corridors are emerging as strategic economic arteries driving industrialization,...

ByafricaprojectJanuary 16, 2026The Engineers Behind Africa’s Tallest and Most Iconic Towers

Across Africa, the rise of tall and iconic towers is reshaping skylines...

ByafricaprojectJanuary 15, 2026